LGBTQ+ History month promotes equality and diversity by “increasing the visibility of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (“LGBT+”) people, their history, lives and their experiences in the curriculum and culture of educational and other institutions, and the wider community.” Some institutions represent this diversity in programs and modules such as Queer Studies, and while it is important to highlight this field of study as a distinct discourse of significance, at Staffordshire we promote inclusivity of diversity and teach the literature of LGBTQ+ writers all the way through our curriculum.

Here are some of the novels, stories and poems English and Creative Writing staff have been reading, researching and teaching at Staffordshire University.

John Cage (1912-1992)

Dr Lisa Mansell

Most people know John Cage as the somewhat cheeky, avant-garde composer of 4’33”, but fewer people know the significant contribution he made to poetry and poetics, recorded over several collections including M: Writings ’67–’72 (1973), Empty Words: Writings ’73–’78 (1979), and X: Writings ’79–’82 (1983).

Cage was a pioneer of procedural, constraint-based and algorithmically generated poetics: a kind of poetry which is composed within a strict confine of rules. One of these algorithmic techniques, called ‘writing through’, entailed a process of selecting the letters which spell out the name of an author then using them as a ‘code’ for selecting words from a novel written by that author, according to strict rules. Cage deployed this procedure for his five ‘write-throughs’ of Finnegans Wake by James Joyce, (Cage mischievously said of this novel, “it’s my favourite book I’ve never read.”) Taking the letters ‘J’ ‘A’ ‘M’ ‘E’ ‘S ‘J’ ‘O’ ‘Y’ ‘C’ ‘E’ as the code, he then applied the process of ‘writing-through’ to Finnegans Wake. The poems were then presented via a reinvention of the ancient mesostich form (pronounced MESS-oh-stick), which Cage called ‘mesostic’. Readers may be already familiar with the acrostic poem, where the beginning letters of each line in a poem form a message or spell out a name; a mesostic does the same thing but with the spelled-out message in the middle of the line. (In case you’re curious, if the code letters are at the end of the line, it is called a telestich).

Cage was also interested in algorithmic process as chance procedures. This time, ‘writing-through’ Thoreau’s Journals. Cage divided the text up into five kinds of material: letters, syllables, words, phrases, and sentences:

“A text can be a vocalise: just letters. Can be just syllables, just words; just a string of phrases; sentences. Or combinations of letters and syllables (for example), letters and words, et. Cetera. There are 25 possible combinations.”

‘Empty Words’, p. 11. (1975)

The next stage in this process, after assigning numerical values to these lexical parts, was to use the I Ching, to produce aleatoric combinations of these words, syllables, letters, and phrases. This results in some of the most strikingly avant-garde and beautiful (in my view) poetry which challenges the way we think about language structures, meaning, and representation.

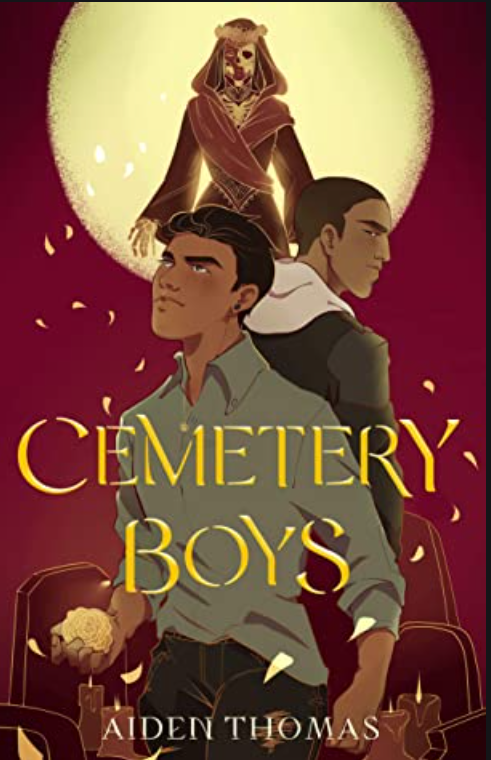

Aiden Thomas, Cemetery Boys (2020)

Amy Blaney

“I’m currently reading Aiden Thomas’ Cemetery Boys as part of a buddy read with some friends. It’s a YA fantasy novel that follows a trans boy – Yadriel – as he attempts to prove himself to his traditional Latinx family. Yadriel’s family are involved in an unusual line of business – the brujos look after the Latinx cemetery and ensure that the souls of the dead pass over and don’t turn maligno, whilst the bruja use the powers gifted to them by Lady Death to heal. Determined to prove himself a brujo, Yadriel sets out to find the ghost of his murdered cousin and set him free – although things don’t go to plan when he instead summons the spirit of local bad boy Julian Diaz – who then refuses to depart this earthly plain until his own unfinished business has been dealt with. Cue the two boys having to learn to work together to defeat an evil that threatens both the world of the living and the dead, all set against the backdrop of a vibrant Latinx culture and featuring heaps of excellent LGBTQIA+ representation. The book is a brilliant mosaic of culture, acceptance, and personal identity (although trigger warnings for instances of dead-naming and misgendering) and I’d strongly recommend it, even to those who don’t normally read YA.

I’d also recommend a visual novel called If Found. It’s available on Steam and Nintendo Switch which focuses upon the experience of a trans woman – Kasio – and her return to her family in rural Ireland. Again, trigger warnings for instances of dead-naming, transphobia, and misgendering – things get very rough for Kasio before they get better – but personally I found this a deeply moving and emotive story that touches on several important LGBTQIA+ issues and examines identity, cultural acceptance, found family, and family relationships in a moving and sensitive way. It also has some gorgeous artwork and a wonderful soundtrack. If you want to find out more about it, you can watch Aoife from Eurogamer conduct a chilled playthrough of the full game at https://youtu.be/nfJLXoGG5PI.”

Chuck Palahniuk, Fight Club (1996)

Dr. Mark Brown

Fight Club was published in 1996, with the film catapulting Chuck Palahniuk and the novel into the cultural spotlight in 1999. Once the film was released, there were many media reports of men taking the fight club – and its famous rules of secrecy – as a blueprint for a version of masculinity constructed around male companionship, violence and heteronormativity which functions as a visceral and authentic contrast to the artificiality of the intense commodity culture in which the IKEA catalogue (remember them?) has become the new pornography. This interpretation of the novel and the film, based on a surface reading of the first section of the narrative, was problematised by Palahniuk ‘outing’ himself as gay on his own website to prevent an interviewer doing it for him in the press.

In the novel, an anonymous narrator unconsciously escapes into the alter-ego of Tyler Durden (played by Brad Pitt in the film), a figure who embarks on a passionate relationship with Marla (played by Helena Bonham-Carter) and establishes the fight club where men punch each other in basements, which then morphs into Project Mayhem; a carnivalesque anti-capitalism and counter-cultural movement.

In the introduction to the American edition of the novel, Palahniuk explains that he constructs a homo-social space because women find this easier, with ‘quilting and mah-jong societies’, but men are limited to sports. While we should be wary of using the author’s biography to interpret a text, there is clearly a willful misreading of the novel by those men who interpret it as a manifesto of physical and sexual dominance, for the establishment of ‘real fight clubs’ and for the ‘pick-up’ culture of the 2000s.

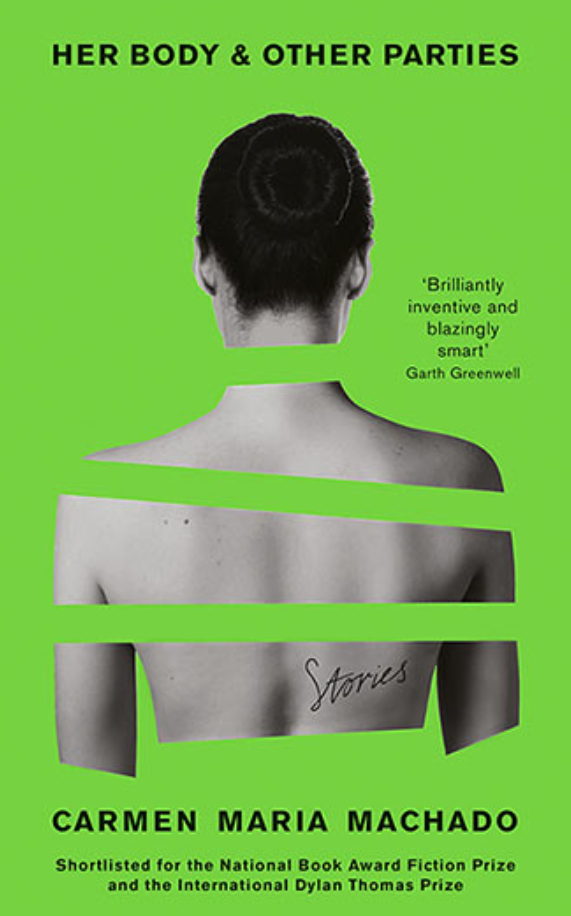

Carmen Maria Machado, Her Body and Other Parties (2017)

Dr. Melanie Ebdon

Dr. Melanie Ebdon has been reading Carmen Maria Machado, Her Body and Other Parties (2017), which depicts several lesbian relationships which are ‘just normalised—there’s no big deal made—they’re just relationships”. Dr Ebdon reads a section from “Mothers” in which the protagonist imagines an idealised future with her new partner. Listen here.

Staff and students at Staffordshire can read the full collection in an ebook, online here.