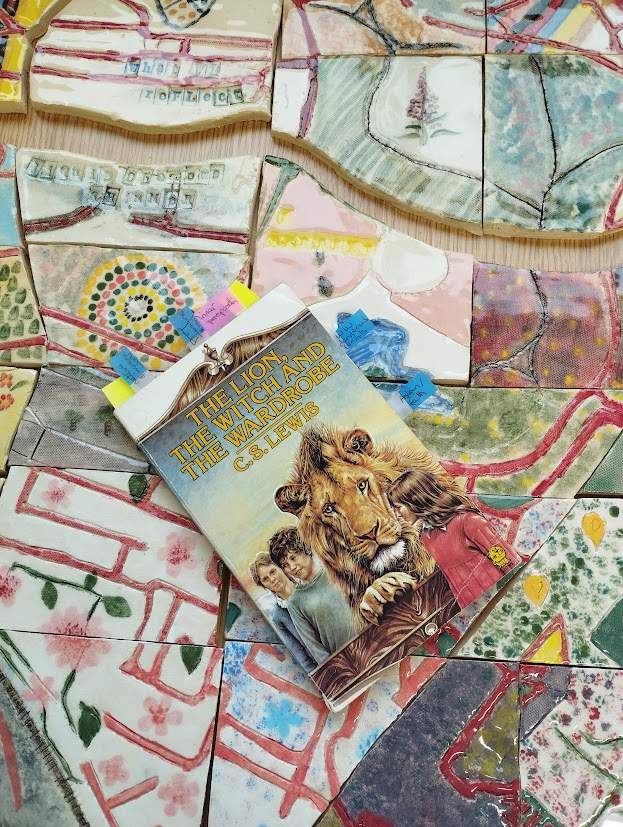

I can trace my career as a literature academic back to my childhood days reading, re-reading and re-re-reading C S Lewis’s The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe. I was transported, along with Lucy and her siblings, to the magical world of Narnia with its talking animals and existential conflict with the White Witch. I was also enthralled by their escape from the humdrum world of reality, something which all children, I think, yearn for. I dabbled a little in the other six books in the series, but none held my attention like LWW.

And now I find it one of the most satisfying books to teach on our Children’s Literature module. Recently I had the joy of exploring the text with visiting Ukrainian writing students. We had a great discussion which revealed the contemporary resonances of occupation and facing down a tyrant. This week it is 75 years since the first publication of The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe.

While it’s always tempting to talk about the realm of the imagination, the magic and the simplistic battle between good and evil, there is so much more to say. There is the context of wartime evacuation and rationing, and the morality of collaboration (Edmund; boooo) and resistance (Aslan; hooray!!!). There is the biblical allegory of Aslan, whose sacrifice and resurrection redeems Edmund (something which we see as adult readers which we may miss as children). Aslan is described as the good news and the light; recognisable from Christian iconography. There are the familiar tropes of children’s literature: adventures without adult supervision; the secondary world of the imagination, where the children can learn important lessons about the adult real (primary) world they are about to enter (for Peter and Susan, the older children); the portal (here, the wardrobe) between these two worlds; and the pastoral world that is an escape from the harsh realities of the mechanistic world of modernity beyond the wardrobe door.

Lewis’s themes tell us much about the time of the book’s creation and the enduring concerns of childhood and its literature. We can see how he smuggles in his Christian message. We can also detect very conventional attitudes to gender, with the boys being brave and active and the girls confined to passive or caring roles. There is also a whiff of colonialism as the exoticised animals wait for the European saviours to arrive and take up their rightful place on the thrones at Cair Paravel. All of the children find the experiences in Narnia transformative, as they learn about personal responsibility, maturity and the expectations of others.

The text is complex in other ways, which we won’t attend to here: Edmund’s betrayal of the other ‘apostles’ at Mr and Mrs Beaver’s house, the White Witch as both a genie (jinn) of Arabic mythology and, simultaneously, Lilith, Adam’s pre-Old Testament first wife in the Garden of Eden. So much to think about, and so little time… But, perhaps, that is where the adventure begins.

English and Creative Writing Department

at Staffordshire University