Everybody agrees that there is a crisis in adult social care. Unlike the National Health Service, there has never been a single national body to look after the needs of people without acute health needs (such as those with long-term disabilities and frail older people) who live in the community. Instead, there has been a patchwork of care supplied by Local Authorities, together with contributions from charities, community interest companies and private providers. In the ‘age of austerity’ the system is approaching a breaking-point as the number of frail older people rises rapidly across the UK, while at the same time there is less money available to Local Authorities for their care. So we are seeing some areas where there are not enough places in residential homes; where home-based care has been scaled back to a minimum; and in one case a council having to be dissolved because it did not have the funds to fulfil its legal obligations.

Clearly, the situation cannot continue indefinitely like this, so new ways of funding social care need to be found. In a major report on the problem, A Fork in the Road (link here: https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/fork-road-social-care-funding-reform) the Kings Fund look at four future funding models. The report concludes that whatever we do, there will be a ‘black hole’ of funding of £1.5billion by 2020-2021, but that extending social care to all the people who we know need it would cost an additional £5.5billion.

In order to afford this level of care, there are only two good options. The government could introduce an extra tax dedicated to social care, providing it on a national basis similar to the NHS. Alternatively, it could increase and extend the personal ‘top up’ contributions so that more individuals have to pay more out of their personal savings for social care. Neither a new tax nor higher contributinos are politically popular, so there is a risk that the government will do nothing, or provide a temporary ‘fix’ that delays the crisis for a few more years. It’s noteworthy that the government’s promised Green Paper (a consultation document) on how we as a society can fund social care has been delayed by more than a year already as all attention is diverted by Brexit.

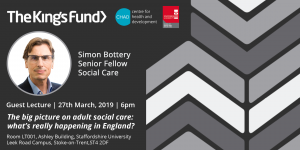

So what is the future for social care? For the first of the CHAD open lectures for 2019 we welcome Simon Bottery from the King’s Fund. Simon co-authored the Kings Fund report and is now working on a follow-up document to be published in mid-April which maps trends in around 20 key indicators in adult social care. He will provide an excellent survey of the current state of social care across the UK and discuss what those trends tell us of the future direction of Adult Social Care in the UK. All are welcome.

Please book your ticket through Eventbrite here: https://www.eventbrite.co.uk/e/the-chad-guest-lecture-march-2019-tickets-57689715492