Immersive simulation – what and why?

In recent years, Staffordshire University has used funding from Health Education England (HEE) to develop innovative, simulation-based teaching approaches.

Simulation enables students to develop contextual and practical skills in a safe learning environment. This is particularly valuable for our healthcare students, who are learning how to work with real patients, but the applications of immersive simulation go far beyond the healthcare setting. For example, students can develop interview skills by talking to an AI-generated virtual human, experience tourist attractions across the globe through a VR headset, or navigate a virtual “crime scene” through 360-degree footage. Immersive technology can also help give online learners a richer learning experience, keeping them engaged with the course.

The HEE funding has enabled the University to invest in specialised software such as Virti and ThingLink. TILE’s Instructional Designer, Simran Cheema, has been working with academic staff across the different schools to use these tools to embed immersive activities into their courses.

The following example explains the process of designing and creating an immersive simulation activity. If you can see the benefits of developing something like this for your own course, details on how to make a start can be found at the end of this post.

Designing an immersive activity – a case study

Simran reached out to academic staff in the Institute of Policing to offer to make an immersive activity to develop incident response skills. In this activity, the “incident” would be a simulation of a vehicle collision, and students would need to take on the role of a police officer attending the scene.

Identifying needs

Before starting design work, Simran had a conversation with course staff to identify their needs from the activity and find out what skills and knowledge should be taught and tested. This was then broken down into constituent steps that would form the overall activity – including interactions with different virtual humans, and 360-degree interactive images.

Simran then identified the technology that would be required to build the activity:

- Virti for the virtual human interactions

- ThingLink to host the whole activity, with 360-degree interactive scenes, embedded Virti characters, and decision-making points with branches to show the consequences of those decisions.

ThingLink also allows for scoring and feedback, to keep the students engaged and on track throughout the simulation, and it also provides the opportunity to track a student’s success through the analytics.

Students would be able to access the simulation freely through a web link, and staff would be able to see analytics data on students’ engagement with the simulation.

Planning phase

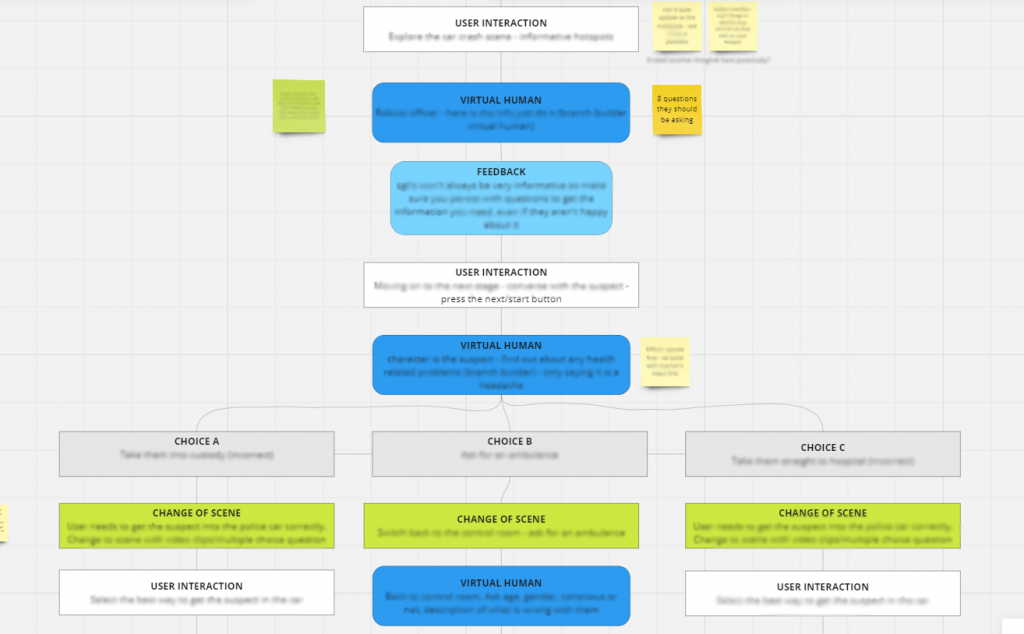

Simran used a different tech tool – Miro – to plan out the activity in detail. Miro’s flowcharting function helped connect the different parts of the scenario and identify where branching and feedback points would be needed.

The students are to follow a linear path through the activity until they encounter a particular character in the simulation – at which point they have a choice of different options for what to do with them. The students do not get immediate feedback on whether their choice was right or wrong – they have to follow through one of different scenarios to show the consequence of their decision first.

Design phase

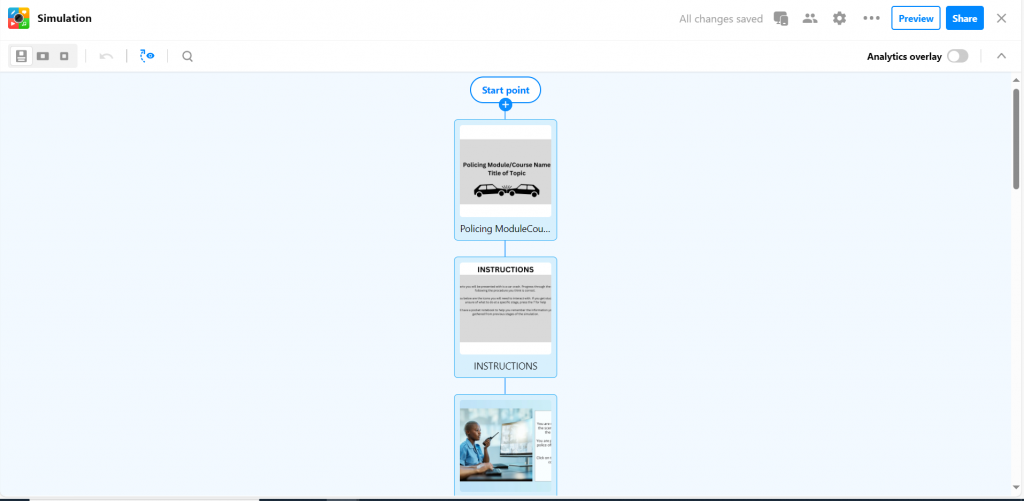

With the flowchart complete in Miro, Simran then started to build the activity using ThingLink’s Scenario Builder. “Simulation” is one of the standard ThingLink templates, but there are also templates for other types of activity such as escape rooms.

Each part of the simulation required some media to be designed and embedded – such as the Virti virtual humans, and the crime scene images.

Simran designed the virtual humans so that students could interact with them in whatever way they preferred – they could speak out loud and the virtual human on screen could respond audibly, or there are text options to read and select from on screen.

The crime scene images – both 2D and 3D – were mainly generated by AI, using the built-in Skybox feature included in the Staffordshire University ThingLink license. However, we do have the in-house technology and simulation settings to capture and record different media to use in the scenario to make it even more immersive for students. For example, for transitions within the activity, video clips of our own simulated court room, custody suite or hospital corridors could be used instead of stock or generated media.

As well as the “action” scenes, Simran also built in space for important conversation points and opportunities to keep students on track with occasional feedback.

Throughout the design process, there was a lot of testing and refining to make sure it was working as intended, and Simran worked closely with the course team throughout.

Could your students benefit from immersive simulation?

If you have some ideas you’d like to explore around immersive simulation, please get in touch with TILE by emailing TILEHub@staffs.ac.uk, or contact Instructional Designer Simran Cheema directly (Simran.Cheema@staffs.ac.uk). We will first identify your needs through an initial consultation and decide on the best approach, and which software to use. We will then support you through the design process as outlined in the case study above.