Finding the Evidence

It was 1995 when journalist and historian Madeleine Bunting reported that, in “a poky attic room, full of dusty potted plant, in the Moscow archives”, she was able to see a copy of a “Top Secret” report regarding atrocities committed in Alderney, a small island in the British Channel Islands that was occupied by the Nazis from 2 July 1940 until 16 May 1945.

In her book The Model Occupation, Bunting outlines how a British military investigator named Captain Theodore Pantcheff arrived in Alderney shortly after the island was liberated, visiting the places where forced and slave labourers were housed, and interviewing witnesses and potential perpetrators.

Bunting was the first of several authors since to have described the findings within the so-called “Pantcheff report”; a document written by Pantcheff in June 1945 that provides a harrowing account of the experiences of thousands of men who were tasked by the Nazis with turning Alderney into “an impregnable fortress”.

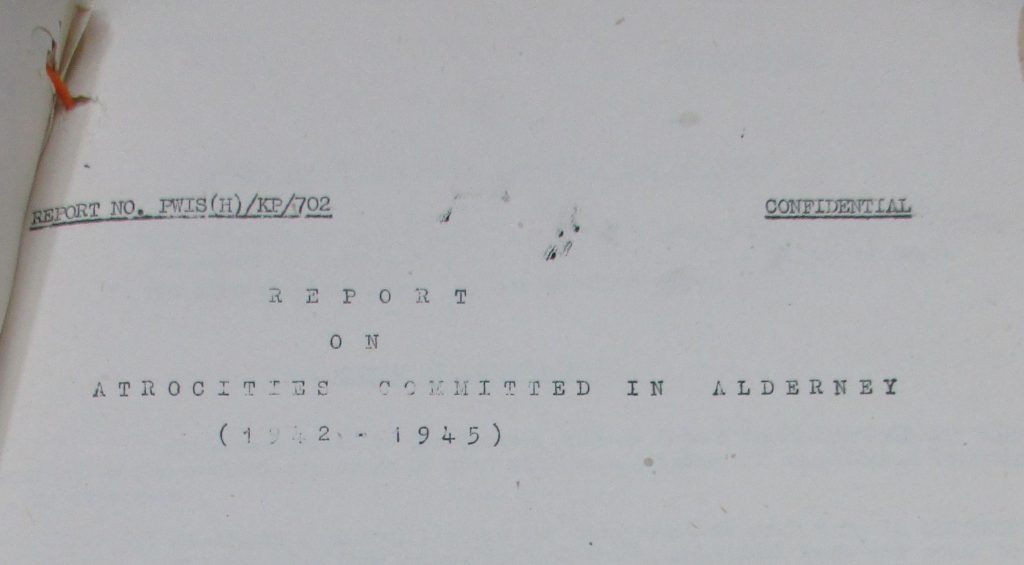

Officially known as Report No. PWIS(H)/KP/702. Report on Atrocities Committed on Alderney (1942-1945), this document consists of Pantcheff’s own observations based on the screening of 3000 witnesses as well as a series of appendices containing details about potential perpetrators, the names of those who were buried on the island, a report on Sylt concentration camp and various testimonies.

Researchers that followed in Bunting’s footsteps also had to rely on the copy in the Russian State Archives (GARF) to describe the crimes committed against the labourers at their places of work and in the complex of concentration and labour camps that housed them. This included Frederick Cohen (The Jews in the Channel Islands during the German Occupation, published 2000), Paul Sanders (The British Channel Islands under German Occupation 1940-1945, published in 2005) and Hazel Knowles Smith (The Changing Face of the Channel Islands Occupation, published 2007).

In 1981, Pantcheff himself wrote a book about the occupation – Alderney: Fortress Island – in which he made extensive use of his own notes and recollections of what happened on the island, albeit with some details diluted compared to his original reports.

British Files?

Many of the publications mentioned above reported that no copy of the “Pantcheff report” existed in British archives. Some authors stated that it had been destroyed in order to “make shelf space”. Others that it remains classified.

It does appears that, until the mid 2000s, this report was not accessible in British archives. However, in 2009 whilst conducting research for my PhD, I came across several reports written by Pantcheff in the National Archives in Kew. One of these was Report No. PWIS(H)/KP/702. Along with its appendices and annexes (contained within a folder called “Analysis”), these documents were original copies of those sent to Moscow. These documents are housed in file WO311/13, one of several archival holdings that related to the “German occupation of Channel Islands: death and ill treatment of slave labour and transportation of civilians to Germany”.

Across numerous other archive holdings in the National Archives, were four other “Periodical Reports” written by Pantcheff, government correspondence, captured German documents and further interviews conducted by Pantcheff and his colleagues. These records built on the work of his predecessors Major Haddock and Major Cotton, who had conducted many interviews prior to Pantcheff’s arrival and who had submitted reports of their own to the British government.

Combined, these materials total thousands of pages. They provide detailed insights into the crimes perpetrated and the investigative process undertaken by Pantcheff and his predecessors.

Copies Closer to Home

In 2010, I also found copies of the Russian Archive documents relating to Alderney in the Island Archives in Guernsey. These took the form of transcripts created by Hazel Knowles-Smith during research for her book The Changing Face of the Channel Islands Occupation: Record, Memory and Myth. These copies were accompanied by the findings of Soviet investigators who had joined Pantcheff on Alderney for a few days in June 1945 in order to establish the extent of the crimes committed against Soviet citizens.

Just as Pantcheff confirmed that “crimes of a systematically brutal and callous nature were committed on British soil”, the Soviet investigators described how acts of torture and ill-treatment had led to hundreds, possibly thousands, of deaths.

Inspiring New Investigations

There is no certainly no denying the importance of the materials in both the Russian and UK archives. They offer unique perspectives on the experiences of the forced and slave labourers, as seen and interpreted by survivors, German personnel and war crimes investigators.

Pantcheff’s main report, and the appendices and statements that accompany it, were central to my decision to carry out non-invasive archaeological investigations at Sylt and Norderney camps as well as the cemetery on Longy Common since 2010. They were vital to my assertion in my PhD thesis (completed in 2011), my book Holocaust Archaeologists: Approaches and Future Directions and a forthcoming volume that I have co-authored with Kevin Colls that further mass and individual burials occurred on the island. Along with other archival documents, they also demonstrated how the British government at the time sought to downplay the crimes committed on the island.

Pantcheff’s report on Sylt concentration and labour camp provided my team and I with important insights into the architecture of mass violence and helped us identify surviving traces of camp buildings and fence lines during archaeological investigations undertaken between 2011 and 2017. The results of our findings were published last year in the journal Antiquity.

Recent “Revelations”

Despite the fact that the Pantcheff report is well known by researchers who have focused on Alderney’s occupation history, in recent weeks a number of media reports have claimed that the secrets in this report can be revealed “for the first time” (e.g Alderney Press, 7 May 2021; ITV, 14 May 2021). They have also claimed that the files are still not available in the National Archives, stating that the “Pantcheff report” remains classified by the British government under the 100 year rule.

However, as shown, this is simply not the case. Researchers have long used the Moscow files to describe the events that took place on Alderney. Likewise, although the report and its accompanying documents did remain classified for some time after World War II, it has now been available for more than a decade in two archives on British soil and has been widely cited.

Of course, it is important to keep revisiting this material in order to provide new perspectives on the crimes committed on Alderney and to honour the memory of those who suffered there. In this regard, it is pleasing to see articles concerning these events getting press attention (and appearing on the front page of the Sunday Times as in the case of one recent article).

However, the accurate reporting of both the contents of the archival material, its availability and how it has been used by researchers is vital for a number of reasons.

As my colleague Gilly Carr and I argued in a co-authored paper in 2016, it is fair to say that the subject of the forced and slave labourer programme on Alderney remains taboo. During my time spent researching on Alderney, I have encountered people who have maintained that we do not have enough archival sources about the forced and slave labourers to document their experiences – and, hence, to commemorate them.

Therefore, I believe that the continued perpetuation of the idea that Pantcheff’s main report remains classified or unavailable in the UK is highly problematic. This view has allowed some people to continue to deny and downplay the events of the occupation. In turn, it has prevented the adequate safeguarding of the sites at which people suffered, such as the camps, burial grounds and fortifications that litter Alderney’s landscape.

Additionally, as Lord Pickles (UK Envoy of Post-Holocaust Issues) recently remarked, “in a world where Holocaust denial, distortion and revisionism is on the increase, we have a duty to provide the unvarnished facts”.

Access the Files

In order to dispel any doubts about its existence in UK archives, and as part of a wider commitment to honouring the victims of Nazi persecution in Alderney, the Centre of Archaeology at Staffordshire University is pleased to provide access to copies of Pantcheff’s main report alongside several other documents from the National Archives, copies of which were sent to Moscow in 1945.

Want to know more:

Read more about the Alderney Archaeology and Heritage Project.

View our publications about forced and slave labour on Alderney

Read an article about our research at Sylt concentration camp in National Geographic

Find out how to watch a documentary about our non-invasive archaeological investigations “Adolf Island”, aired by the Smithsonian Channel in 2019

Professor Caroline Sturdy Colls and Associate Professor Kevin Colls will publish their book “Adolf Island”: The Nazi Occupation of Alderney later in the winter of 2021/22 with Manchester University Press.