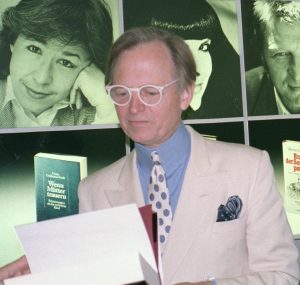

Tom Wolfe, the American writer, has died this week at the age of 88. He is known as the author of two significant novels: The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test (recounting his experiences with Ken Kesey and the Merry Tricksters in the 60s) and The Bonfire of the Vanities (made in to a movie starring Tom Hanks, Bruce Willis and Melanie Griffith in 1990). But his greatest influence has been on the writing that he termed New Journalism. The movement has given us Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood (about a quadruple murder in Kansas), Michael Herr’s Dispatches (recounting his experiences of reporting the Vietnam war) and Hunter S Thompson’s Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas (an account of a drug-fueled trip to report on a motorbike race in the desert) – these works have the quality on a ‘non-fiction novel’ (Capote’s term) because they reimagine or report upon actual events. Wolfe anthologised the writing of these authors, himself and others in The New Journalism (1975) and gave a name to a style of writing that had emerged as a response to the 1960s. Wolfe claimed that the novel was bankrupt, and called instead for a form of writing that was as accurate and neutral as journalism, but as creative and involved as the novel written by the realists and naturalists of the nineteenth century (Balzac, Zola and Dickens). Wolfe rejected the experimentation of postmodernity, preferring the conventional linearity and representational strategies of realism, seeing in it an immediacy and emotional involvement that gives the work greater authenticity. Readers of The Bonfire of the Vanities (the topic of a chapter I am writing for a new monograph on the contemporary New York novel) will know from its epic scale and reach that it has more to do with Dickens’ panoramic views of London than it does with the fractured narratives of contemporaries such as Thomas Pynchon or E L Doctorow, whose experimentation he rejected as artificial.

English and Creative Writing Department

at Staffordshire University