In his last novel, Baumgartner, Paul Auster contemplated the nature of loss and mortality. Auster had been ill with lung cancer for some time before his death this week, and this novel now, in retrospect, has the feel of a love letter and a farewell to his wife, the novelist and academic Siri Hustvedt. Death has haunted Auster and his work. In the early autobiographical meditation on writing, The Invention of Solitude, Auster recounts the tale of his grandmother shooting his grandfather and the effect on him of the early death of his own father. In The New York Trilogy, the novel that brought him to international attention, Quinn, the central character in the first part of the trilogy, has become isolated and alienated from his New York environment by the unexplained deaths of his wife and son. Quinn recounts how he can still feel the impression of his young son, Daniel, on his chest. Auster’s own son, Daniel, died in adulthood of a drugs overdose. Auster’s life, then, was lived in the shadow of death and tragedy, and we can see more than the traces of that experience in his novels.

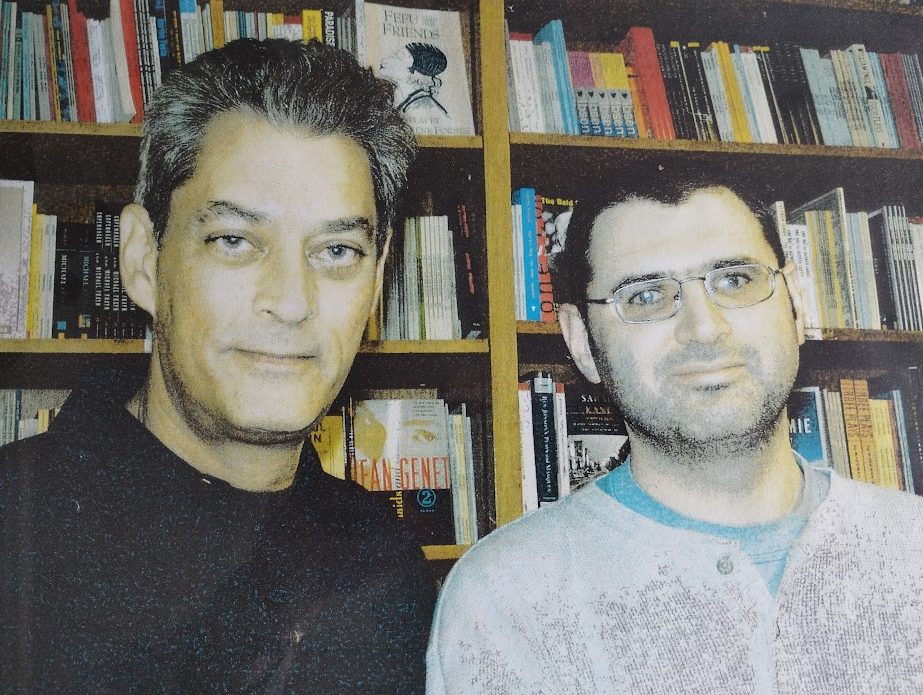

That isn’t to say that his substantial body of work will only be remembered for its focus on loss. Many of his works employed his beloved New York City as both a setting and a character. I met him on a research trip to the New York in December 2001, just weeks after 9/11, and we shared a cab back from Manhattan to Park Slope in Brooklyn, where he lived in an impressive brownstone with Hustvedt. We looked back from the cab window as we crossed the East River and mourned the loss of the towers and the dead of that terrible day.

Auster’s early life was peripatetic and adventurous. He grew up in New Jersey and went to Columbia University in New York. He was fluent in French and spent time in Paris on his degree and returned there to work as a translator. He collected and edited the works of French modernist poets in translation, particularly Mallarmé. At the same time he was writing his own poetry, which he considered his best work. The poems are small, taut, and intense. He also worked on merchant ships and as a census collector back in the US. These episodes provided him with rich material to shape his characters.

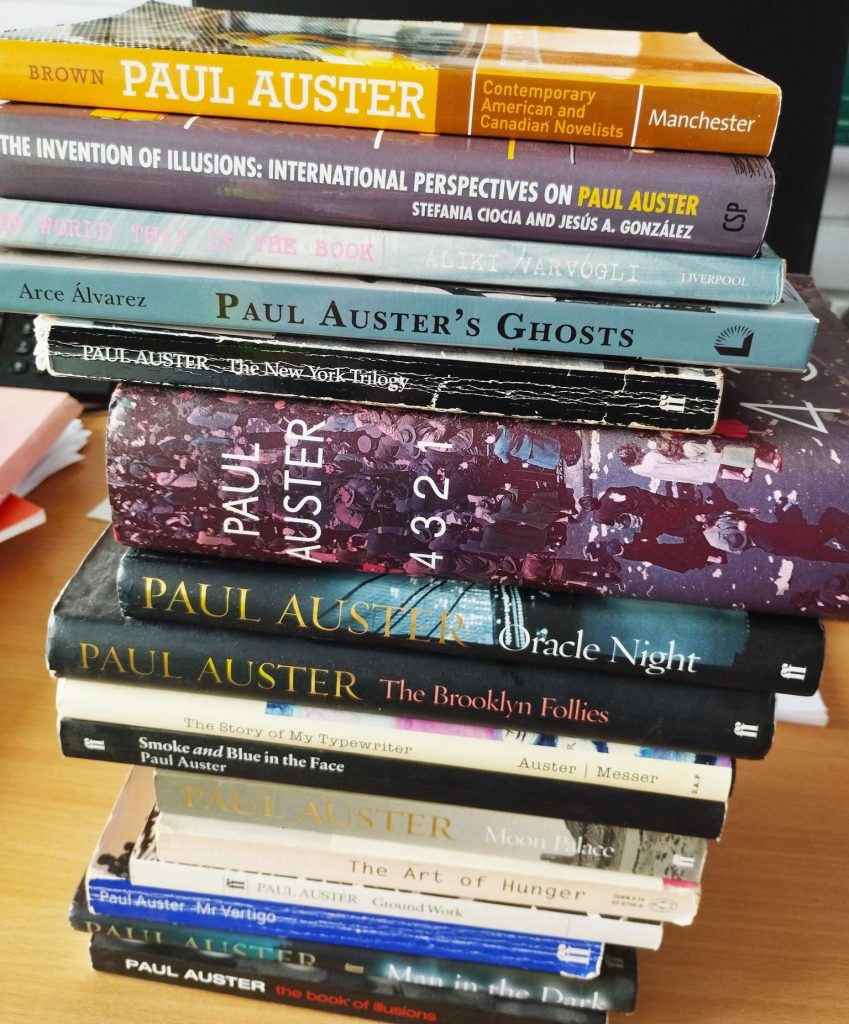

It is possible to distinguish – a little arbitrarily, perhaps – four phases to Auster’s career. The work has moved from poetry and non-fiction (collected in Ground Work and The Art of Hunger), through the early fictions (The New York Trilogy, Moon Palace and others), to the films of the mid-1990s, and subsequently to the later novels (including The Book of Illusions – my favourite from this period – and 4321). Each phase is distinct in the form and the themes the work interrogates, while key themes of language, identity, solitude, and the power of writing and storytelling are held in common, explored, and developed.

One of the most distinct features of Auster’s early work is the way the lives of his writer-characters frequently collapse into the lives of the characters they create, consistently calling into question the boundaries of where the “real” world ends and the fictional world begins and, in a postmodern way, questioning the capacity of literature to represent reality at all. Auster’s struggle toward reality is problematised by anxieties about the capacity of language to represent, language as a way of being in the world.

Auster’s films, Smoke and Blue in the Face (1995), represent a shift in both medium and tone. There is a warmth and optimism about the films which is felt only occasionally in the preceding novels. This optimism expresses itself through community and, in particular, in the representations of Auster’s own home borough, Brooklyn.

After the films, Auster’s fiction takes on a distinct change in subject matter, tone, and address. Two themes dominate this body of work. The idea of a place of imagination to escape to and remake the self comes to dominate Timbuktu and 4321, while an exploration of the genesis of a story and the essence of literary art are at the center of Oracle Night and Travels in the Scriptorium.

Auster’s body of work is impressive and it reminds me of the work of Fanshawe in The 3rd part of the Trilogy, which fills two suitcases and is as heavy as a man. All told, there are sixteen novels, nine non-fiction and autobiographical works, six collections of poetry, four films and many collaborations.