It is a truth universally acknowledged that any blog post about Jane Austen must begin with an awkward homage to her best-known novel, Pride and Prejudice (1813).

It is also a truth universally acknowledged that, since her death on 18 July 1817, aged only 41, many writers have sought to capture the magic of Austen’s writing, and to pay tribute to her through imitations, sequels, retellings, and reimaginings of her work.

So, in honour of Austen’s birthday (16 December 1775), I wanted to share six of my favourite literary reimaginings and retellings of her most famous work. For keen readers of Austen, I hope these will share new light upon a favourite novel. For those yet to become acquainted with her, maybe these will serve as a means of introduction? For me, the versatility and variety of the following books demonstrates the genius of Austen’s characterisation and plotting, the timelessness of her themes, and the resonance that the stories she told continue to have for thousands of readers today.

The Other Bennet Sister by Janice Hadlow

Published in 2020, Janice Hadlow’s The Other Bennet Sister tells the story of Mary, middle of the five Bennet girls, plainest of them all and, arguably, the most overlooked by both her family and her creator. An introvert in a family of extroverts, Mary is very much a peripheral figure within Pride and Prejudice – and is usually depicted alongside Mr Collins as a figure of fun in the many film and TV adaptations. Hadlow, however, manages to convey the depth of Mary’s character, showing us a young woman who, though different from her siblings, has no less passion and no fewer dreams. For those new to Austen, this lively modern novel may encourage you to read Pride and Prejudice the first time whilst, for Austen-lovers, seeing Lizzie, Darcy, Jane, Lydia et al. from Mary’s point of view provides a chance to reflect on the value of wealth and beauty from the perspective of a young woman without either.

Ayesha at Last by Uzma Jalaluddin

Set in modern-day Canada, Uzma Jalaluddin’s Ayesha at Last takes the plot and themes of Pride and Prejudice and combines them with a modern Muslim romance. Heroine Ayesha Shamsi has set aside her dreams of becoming a poet to pay off her debts to her wealthy uncle. Adding to her problems, she’s still single whilst, as her boisterous family are always reminding her, her flighty younger cousin Hafsa is close to rejecting her one hundredth marriage proposal. When Ayesha meets Khalid, she finds herself irritatingly attracted to someone whose conservative and judgemental nature means he looks down on her choices and dresses like he belongs in the seventh century. Yet unbeknownst to Ayesha, Khalid is also wrestling with what he believes and what he wants. Despite announcing a surprise engagement to Ayesha’s cousin Hafsa, Khalid just can’t get the outspoken Ayesha out of his mind. Ayesha at Last is a lot of fun and, for me, demonstrates that the themes and concerns of Austen’s novel resonate not only across time but also through cultures. Another modern re-telling worth a shout is Curtis Sittenfeld’s Eligible, which moves the action to modern-day Ohio and adds in a dash of reality TV.

Death Comes to Pemberley by P. D. James

Pride and Prejudice…and murders! Queen of Crime P. D. James brings her expert plotting and fine eye for detail to Pemberley in this elegantly gauged tribute to Austen’s vitality. Set in 1803, the orderly world that Darcy and Elizabeth have created for themselves is threatened when, on the eve of their annual ball, Lydia Wickham – Elizabeth’s unreliable sister – stumbles out of a carriage screaming that her husband has been murdered. James’s pastiche of Austen is laced with authentic smatterings of Austen’s trademark wit, combining this with a thoroughly researched portrait of Georgian law and order. As a crime story, Death Comes to Pemberley is deeply enjoyable in its own right but, for me, it also demonstrates the versatility of Austen’s imagination and the way in which her sharp observations of society and wicked sense of humour underpin a genre so seemingly disparate as crime fiction. For more genre-bending Austen, fantasy fans might also like to look up Heartstone by Elle Katherine White for Pride & Prejudice with additional dragons.

Pride and Prejudice and Zombies by Seth Grahame-Smith

Okay, so I mostly put this one in here because it’s Pride and Prejudice WITH ZOMBIES. And what isn’t to love about that as a concept? Look beneath the parodic swordfights and ignore the ninjas for a moment (because yes, there’s also ninjas in this one), however, and you’ll find a wry commentary on literary expectations and Regency-era society. The academic literature on this adaptation of Austen’s classic is, honestly, very interesting and considers everything from the meaning behind Charlotte Lucas’s zombification to the importance of sword-wielding heroines for modern female readers. For those seeking to move beyond Darcy and Elizabeth, Grahame-Smith added a kraken and some pirates to Austen’s first published novel to create Sense and Sensibility and Sea-Monsters, and wrote a sequel called Pride and Prejudice and Zombies: Dreadfully Ever After.

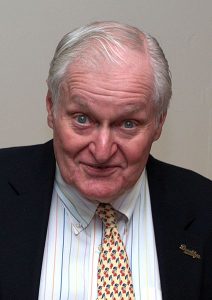

What Matters in Jane Austen by John Mullen

Mullen is a Professor of English at University College London and has taught Austen to university students for over a quarter of a century. Distilling that knowledge into a lively and accessible piece of literary criticism, What Matters in Jane Austen endeavours to answer twenty crucial puzzles about Austen’s work including, How Much Does Age Matter?, Do We Ever See the Lower Classes?, and Is There Any Sex in Jane Austen? Mullen is an entertaining and knowledgeable guide – especially to Austen’s lesser-known works – and his book is the perfect primer for revisiting the novels with a fresh critical eye.

Longbourn by Jo Baker

Speaking of the lower classes, who does wash the mud of Elizabeth Bennet’s skirt after she troops over to Netherfield Park to appal polite society? The answer, for Jo Baker at least, is Sarah: one of the housemaids at Longbourn, the Bennet family home. Baker’s eye for detail undercuts the televised romanticisation of Austen’s era, depicting not only the lives of those who do the dirty work that enable Austen’s polite heroines to take tea or go to balls, but also reflecting on the turbulent politics of the era and, poignantly, on the aftereffects of the Napoleonic Wars.

These are just a smattering of many adaptations and appropriations of Austen’s work but, hopefully, they’ve given you a flavour of just how resonant her writing remains. More than 200 years after her death, Austen’s novels and short fiction continue to be read and enjoyed by readers across the globe. And whilst F R Leavis saw Austen as one of the cornerstones of the ‘canon’ of English Literature, for me, her work resonates not because of its universality or intrinsic brilliance (although I do think Austen is brilliant) but because of the way that her intricate examinations of love, marriage, family, society, and commerce invite new perspectives, new approaches, and new imaginings that encourage us to reflect not only on the period in which she lived and wrote but on our own experiences and society today.

Amy Blaney