Members of the Staffs Uni Humanities Society were at the Royal Exchange in Manchester for their highly acclaimed production of Macbeth.

Society chair, Joe Ward, said: ‘this production just blew me away. We had a great, including sushi’.

The Nobel Laureate, Toni Morrison, has died at the age of 88. She was educated at Howard and Cornell Universities, going on to work as an academic, critic and activist as well as one of the most influential novelists of her own and subsequent generations. For her writing, she won the Pulitzer Prize for Literature in 1988 and the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1993.

Morrison’s body of work is concerned with how the unvoiced, the silent and the invisible of history bear witness to and give testimony about their suffering and oppression.

This leads us to consider how subsequent generations incorporate the memory of their ancestor’s suffering into their own histories and how they make sense of the present with those histories in mind.

Morrison’s best known novel is Beloved, published in 1987.

That Beloved has at least two presents prompts the reader to consider how the past acts on the present and how the traumatic events experienced in one can be both supressed and revealed by memory in the other.

Throughout the novel, Sethe struggles with memory as a site upon which the horrors of slavery must be both ‘beaten back’ and negotiated in the present.

The horrors of slavery are inscribed upon the bodies of slaves, and so their corporeal, bodily presence in the world stands as its own testament to their suffering.

The beating that Sethe receives for sending her children to safety, the tree that is inscribed on her back by the whip, is a physical manifestation of the scars of slavery. Many other physical scars – including where the saw cut Beloved’s throat – manifest themselves in this narrative.

But it is the mental and emotional scars that are Morrison’s primary concern and the capacity of the tramautised individual and community to come to terms with brutality and suffering.

A book about slavery read by millions of people, studied on a majority of English degrees across the world, puts slavery at the centre of a cultural debate in a way that politicians and campaigners had not been able to.

It does so by humanising the suffering that had affected so many millions of people. The novel tracks the individual experience of an institution that was industrial in its scale, economic in its organisation and supported by federal legislation

The novel itself emerged from a fragment of history that Morrison encountered while researching a book of blacks on record – in print, song, newspapers, photographs – a sort of informal history.

She found newspaper accounts of Margaret Garner who killed her child to prevent her being returned to slavery by vigilante slave hunters. The event was immortalised in Thomas Satterwhite Noble’s 1867 painting, The Modern Medea.

The book is almost symmetrical, balanced around the revelation of the incident at the very centre of the narrative – the infanticide

Morriosn doesn’t use partial revelations, hints and subtle developments as conventional aspects of literary suspense, though. Instead, she uses these evasions to signal both the unimaginable sadness of the event and the nature of Sethe’s subsequent relation to it – she can neither forget what she has done to her child, but neither can she bring herself to recall it. Memory must be a battle between supressing and memorialising.

There is another motivation to this structure of repetitions and developments. One of the ways in which the slaves communicate with each other is through song. Owners and overseers see these songs as the rhythms of work and a sign of a happy slave population, but they are radical challenges to the authority of the oppressor, carrying messages of potential escape as well of support for those who can bear their condition no longer.

Slave spirituals, as the songs became known, have a pattern of repetitions and developments, of call and response. It has become a signature for expression and representation in African American culture. You find the cadences of call and response everywhere in black American culture; from gospel and blues, to preaching, to the rhetoric of black political leaders.

Morrison did a great deal to raise the voice of African Americans through difficult times, but her presence at Obama’s inauguration demonstrated how influential her own has been in giving voice to the unvoiced. Her novels remain as a lasting testament to her influence and genius.

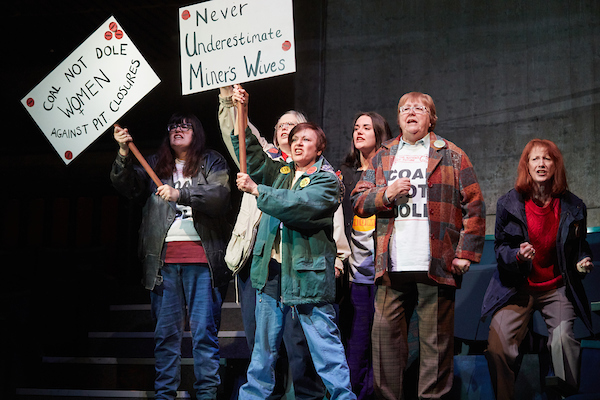

The New Vic Theatre in North Staffordshire has a proud tradition of politically and socially engaged drama that reflects the lives of the communities it serves. Under its founding artistic director, Peter Cheeseman, the theatre has created a series of original productions which both documented and dramatised the industrial struggles of the area. The Knotty, their first documentary theatre production, traced the lives of railwaymen on line which served the 6 towns of the Potteries. Later documentary plays, employing what became known as the Stoke Method, sent the cast out into the community to interview people directly involved in the events being portrayed. I Don’t Want to Set the World on Fire recorded the lives of the Roses of Swynnerton working in a local munitions factory in WW2. The Fight for Shelton Bar, perhaps the most innovative documentary, traced the battle between British Steel and the workers over the future of a steel works in the city as it happened, with updates from the unions committee at the end of each show. The struggles over the mining industry in the area were portrayed in Nice Girls, the account of 4 women occupying Trentham Colliery a decade after the strike of 1984. More recently, Maxine Peake’s Queens of the Coal Age dramatised similar events in the Lancashire coalfield.

The Vic’s current production is a stage version of the hit 1994 film, Brassed Off. A decade after the strike, the miners of Grimley face an existential threat to the their livelihoods and their community as the Coal Board offer them £23000 each to accept closure now, or take a lesser payout later on. At the same time, the colliery band are on the verge of their greatest achievement ever, with the chance to play in the National Finals at the Royal Albert Hall. But can you have a colliery band without a colliery? The play traces the effects of community divisions and poverty on real people in an environment that they can neither predict nor control, as well as the solidarity and identity that music and community can generate.

Director Conrad Nelson expertly blends the cast with the amazing TCTC brass band and community actors. The cast is so strong that its is impossible to pick one out for particular praise. I remember The Daily Mail describing the film as (something along the lines of) over-sentimental, anti-Thatcher propaganda – now that’s the sort of thing that gets an audience on their feet round here.

Staffs Uni English graduate, Ed Hilton, is launching his play, Pit Boy to Prime Minister, at the New Vic Theatre on May 25th.

The play follows the life of Staffordshire miner, Joseph Cook, who left Silverdale for Australia in 1885. After working in mining there, he became involved in Labour Party politics and progressed from the New South Wales State Assembly to become Prime Minister of Australia in 1913.

Ed is seen here with Malcolm Henson from North Staffordshire Press and the script.

Ed graduated from Staffs in 2017 before going on to do a Masters at Keele. Once his play has been realised on the stage, Ed intends to go in to teaching where his background in both English and Creative Writing will help to enthuse a whole new generation of literature scholars.

Our warmest congratulations go to Ed.

English graduate, Jack Hawkins, recently met Bret Easton Ellis at the book tour to promote his new novel, White. Jack got his taste for BEE reading American Psycho on the Contemporary American Fiction module.

Jack writes: “I’m enjoying White. It’s part memoir, part diatribe against political correctness, safe spaces and the ‘cult of likability’. His perspectives on film and writing American Psycho are interesting, too. A lot of it has been taken from his Patreon podcast.

There’s a great article in The Guardian about the publication of the recent book. It’s interesteing to read about the circles Ellis was moving in during the 1980s. He knew Jay McInerney (Bright Lights, Big City), Tama Janowitz (Slaves of New York) and Jonathan Lethem (Motherless Brooklyn) – all great writers and books.

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2019/apr/28/bret-easton-ellis-millennials-white-interview

Let us know your news.

Students from Stoke on Trent high schools visited the university to celebrate their entries to the Sentinel Big Read competition. All year 9 pupils in the city received a book of cartoons inspired by childhood reads, and the Big Read competition continued the theme.

Pupils visiting the uni for the presentation of prizes took part in Masterclasses from Comic Arts and Creative Writing. Thanks to 2nd year students Jordan and Romisa who helped the pupils create characters for new stories.

Congratulations to everyone who took part, was nominated or won a prize.

Read more here https://www.stokesentinel.co.uk/news/stoke-on-trent-news/meet-prize-winning-comic-strip-2745293

Students on the Victorian literature module visited the Gladstone Pottery Museum in Longton to learn about Dickensian working conditions and the pottery industry of Arnold Bennett’s Anna of the Five Towns. A guided tour from one of the museum’s experts helped contextualise child labour, working conditions, labour organisation and how pottery workers were paid, along with many other things. This picture shows students outside one of the distinctive bottle ovens which feature across Stoke’s cityscape.

Northern Broadside’s Much Ado About Nothing, which we saw last week as part of the Shakespeare module, transplants the action to WW2 England. Beatrice becomes a land girl, in wellies and sensible tweed, while Benedick is in the uniform of the RAF. Robin Simpson and Isobel Middleton in these roles absolutely steal the show, but they are wonderfully supported by a cast which brings the play to life. Alongside the verbal jousting between the will-they-won’t they central characters which characterises Shakepeare’s romantic comedies, there are delightful interludes of big band jazz, barber shop quartets, dancing and camp comedy.

The Guardian, in a 4 star (out of 5) review, describes how the company make ‘dynamic use of the in-the-round space and, for all the Dad’s Army daftness, venture boldly into the play’s darker corners of treachery and deceit’.

It was fantastic to be back at the old Spode factory for some ‘site specific’ or ‘found space’ drama. In Hot Lane, Claybody Theatre and English and Creative Writing Honorary Doctor, Deborah McAndrew, develop many of the characters we met in last year’s Dirty Laundry. The play is billed as ‘passion and betrayal in the six towns’ and it traces how the mundane lives of an industrial community contain as much drama as you find anywhere. Set in the 1950s, the drama explores how the war disrupted moral codes and how the intervening years have introduced technological innovation, but very little social progress for women. The local colour and a palpable sense of the time are created by dance hall scenes brought vividly to life by community dancers. The simple design moves us seamlessly between the domestic spaces of the pottery owner and the homes of ordinary pottery workers.

Angela Bain superbly reprises her role as community matriarch, Frances from Dirty Laundry, as does Philip Wright as Pottery owner, Richard Wareham, which is not to diminish the excellent performances of the whole cast. The Potteries accent is hard to master unless you are born to it, but the whole cast transport the audience to 1950s Burslem with ease (Philip Wright, some-time ago, told me that he’d learned the accent from watching videos of Port Vale’s Tom Pop – now there’s a Stoke accent). The students who accompanied us had a great time and were taken with the atmosphere of live theatre. Early next year, we will be visiting the New Vic for Broadsides’, Much Ado.. (directed by Claybody’s Conrad Nelson).

Deborah tells me that she is considering a prequel: this is box-setting at a very gentle pace!