(Mark and Lisa)

Lawrence Ferlinghetti was a friend and a publisher to the writers of the Beat Generation, and an influential poet who was both critically and commercially successful. His bookshop, City Lights, became the epi-centre of the San Francisco phase of the Beat movement when it’s major figures, particularly Ginsberg and Kerouac, moved from New York to the West coast. City Lights has been open in the same premises since 1955 and along with Shakespeare and Co in Paris – which had been an inspiration for Ferlinghetti – is one of the best known and most inviting bookshops on the planet. San Francisco was an enclave of non-conformist culture at the time, possibly because of the siting of a camp for pacifists and conscientious objectors nearby during the war. Once released back into society, these renegades fostered a community of radicals and rebels. Ginsberg and Kerouac were drawn to San Francisco by the promise of literary freedom and like-minded artists. The little black and white covers of the Pocket Poets series have become a design classic and have remained unchanged for nearly 70 years. The shop, too, remains a beacon to poets, travellers and those with a love of the writing of the Beats.

The City Lights Books Pocket Poets series was thrust into the glare of publicity by Ginsberg’s collection, Howl and Other Poems. Ferlinghetti had seen Ginsberg read the title poem at a now famous reading at the Six Gallery in October 1995 and contacted the young poet to arrange to publish his work. The content was scandalous for the time, a period of political and social conformity enforced by a Cold War culture that valued a narrow consensus that privileged an anti-communist, white, middle-class, male hegemony. Ginsberg’s famous opening lines, ‘I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by madness, starving hysterical naked,/dragging themselves through the negro streets at dawn looking for an angry fix’, challenged everything that the mainstream cherished. His portrayal of angelheaded hipsters ‘with dreams, with drugs, with waking nightmares, alcohol and cock and endless balls’ attracted the attention of the SFPD, who failed to have the book banned for obscenity and succeeded only in bringing a radical new poetry to the attention of a much wider readership. The Beats became internal exiles, attacking what they saw as America’s conformity, inequality, consumerism and warmongering. The Beat writers were in search of ‘IT’ – the soul of jazz, orgasm, the freedom of the streets, the heightened consciousness of drugs – and Ferlinghetti was an important guide on that journey. Ferlinghetti was himself a poet of some note and he toured the world with Ginsberg, bringing Beat poetry to the Beatniks and hippies of the 60s – including a famous reading at the Royal Albert Hall in 1965.

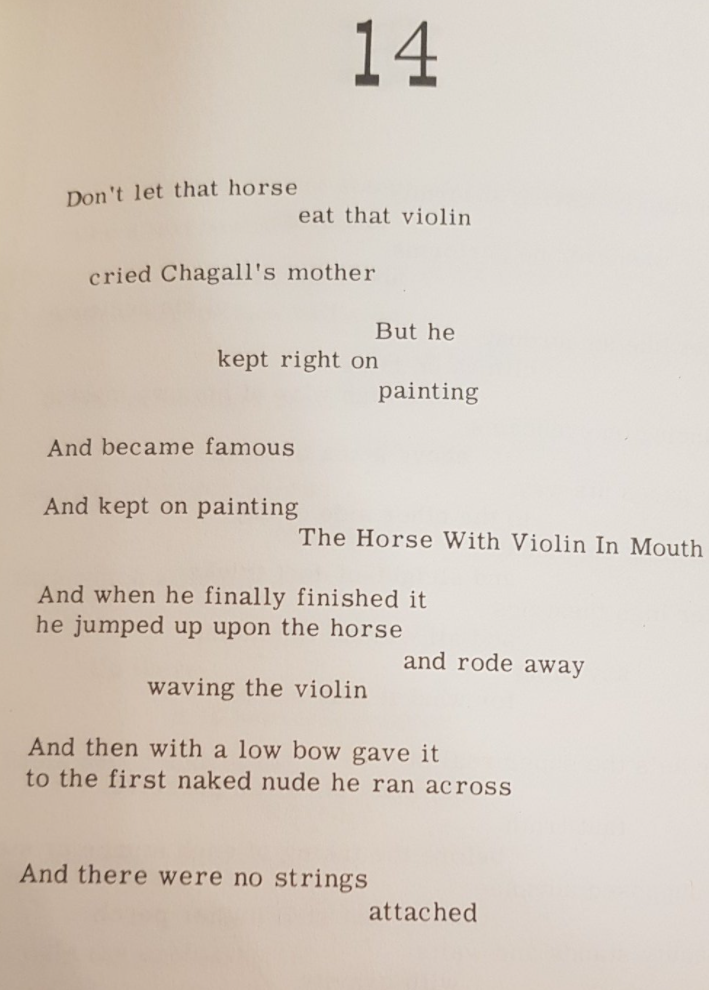

Ferlinghetti’s iconic 1958 collection, A Coney Island of the Mind, remains one of the bestselling poetry collections. (link: https://www.theguardian.com/books/booksblog/2008/aug/19/revisitingconeyislandofthe) . It is a masterwork of lyricism and realism which weaves together motifs of music and the clothes-pegged, telegraph-wire strewn cityscape. In many ways, this collection is about lines: telegraph lines, poetic lines and musical lines reaching from the improvised line of jazz, to birdsong, to more classical structures of phrase and cadence:

The poet’s eye obscenely seeing

sees the surface of the round world

with its drunk rooftops

and wooden oiseaux on clotheslines

and its clay males and females

with hot legs and rosebud breasts

in rollaway beds

City boundaries and lines which demarcate social spaces are blended and problematised in the ‘plastic toiletseats tampax and taxis’ (note the generous texture of internal consonance and alliteration) which nestle amoung ‘stemheated cemeteries’ and ‘protesting cathedrals’ to form a ‘surrealist landscape’. The projective, ‘open field’ lines which arc across the page architecture the poetic space and unleash a ‘wired’ energy through this opening sequence of twenty-nine poems.

Ferlinghetti lived in the bohemian North Beach area of San Francisco up to his death last week at the age of 101.