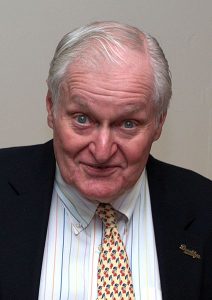

We wake to the sad news that one of our greatest modern poets, John Ashbery, has died aged ninety.

He was a leading figure of the New York School of poetry in the 1960s, a group influenced by modernist and contemporary art (especially abstract expressionism and surrealism). The work that emerged from this movement was wide-ranging; forms of pastiche, non-narrative and anti-narrative text, a simultaneous return to and rejection of form all problematised the discipline of poetry—and in a good way. Complex new poetry for a complex new, postmodern world. An interest in contemporary culture provoked poems about the banal, every day, sometimes the throw-away. Art is life, and sometimes, life is dull. No more grand subjects and narratives, just life.

This is neither an obituary nor essay; it’s a remembering of my first encounter with Ashbery, and not an easy one to recollect since his poetic work has been so prominent in the study of contemporary poetics, but I think I can pin it down to a balmy late September in a seminar room when our tutor gave us crumpled photocopies of “The Skaters” (1964):

These decibels

Are a kind of flagellation, an entity of sound

Into which being enters, and is apart.

Their colors on a warm February day

Make for masses of inertia, and hips

Prod out of the violet-seeming into a new kind

Of demand that stumps the absolute because not new

In the sense of the next one in an infinite series

But, as it were, pre-existing or pre-seeming in

Such a way as to contrast funnily with the unexpectedness

And somehow push us all into perdition.

The direct address, themes concerning sound and music and the rush of rich images made this early encounter with Ashbery’s text a meaningful touchstone for much of my later research concerning poetry, music, sound, and the every day. I return to Ashbery again and again in reading, research and in teaching (some of our students will know well the famous “Popeye” sestina: “Farm Implements and Rutabagas in a Landscape”).

For more information about Ashbery, explore the online collection archived at the Poetry Foundation

To read and listen to, in Ashbery’s own voice, “The Skaters” visit the archive at Penn Sound.