The Nobel Laureate, Toni Morrison, has died at the age of

88. She was educated at Howard and Cornell Universities, going on to work as an academic, critic and

activist as well as one of the most influential novelists of her own and subsequent

generations. For her writing, she won the Pulitzer Prize

for Literature in 1988

and the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1993.

Morrison’s

body of work is concerned with how the unvoiced, the silent and the invisible of history

bear witness to and give testimony about their

suffering and oppression.

This leads us to consider how

subsequent generations incorporate the memory of their ancestor’s suffering

into their own histories and how they make sense of the present with those

histories in mind.

Morrison’s

best known novel is Beloved, published in 1987.

That Beloved has at

least two presents prompts the reader to consider how the past acts on the

present and how the traumatic events experienced

in one can be both supressed and revealed by memory in the

other.

Throughout the novel, Sethe struggles

with memory as a site upon which the horrors of slavery must be both ‘beaten

back’ and negotiated in the present.

The horrors of slavery are inscribed upon

the bodies of slaves, and so their corporeal, bodily presence in the

world stands as its own testament to their suffering.

The beating that Sethe receives for

sending her children to safety, the tree that is inscribed on her back by the

whip, is a physical manifestation of the scars of slavery. Many other physical

scars – including where the saw cut Beloved’s throat – manifest themselves in

this narrative.

But it is the mental and emotional

scars that are Morrison’s primary concern and the capacity of the tramautised

individual and community to come to terms with brutality

and suffering.

A book about slavery read by millions

of people, studied on a majority of English degrees across the world, puts

slavery at the centre of a cultural debate in a way that politicians and

campaigners had not been able to.

It does so by humanising the suffering

that had affected so many millions of people. The novel tracks the individual

experience of an institution that was industrial in its scale, economic in its

organisation and supported by federal legislation

The novel itself emerged from a

fragment of history that Morrison encountered while researching a book of blacks on

record – in print, song, newspapers, photographs – a sort of informal history.

She found newspaper accounts of Margaret

Garner who

killed her child to prevent her being returned to slavery by vigilante slave

hunters. The event was immortalised in Thomas Satterwhite Noble’s

1867 painting, The Modern Medea.

The book is almost symmetrical, balanced around the

revelation of the incident at the very centre of the narrative – the

infanticide

Morriosn doesn’t use partial revelations, hints and subtle

developments as conventional aspects of literary suspense, though. Instead, she

uses these evasions to signal both the unimaginable sadness of the event and

the nature of Sethe’s subsequent relation to it – she can neither

forget what she has done to her child, but neither can she bring herself

to recall it. Memory must be a battle between supressing and memorialising.

There is another motivation to this structure of repetitions

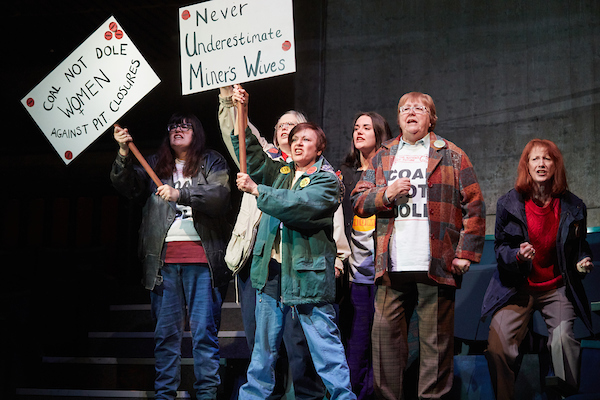

and developments. One of the ways in which the slaves communicate with each

other is through song. Owners and overseers see these songs as the rhythms of

work and a sign of a happy slave population, but they are radical challenges to

the authority of the oppressor, carrying messages of potential escape as well

of support for those who can bear their condition no longer.

Slave spirituals, as the songs became known, have a pattern

of repetitions and developments, of call and response. It has become a

signature for expression and representation in African American culture. You

find the cadences of call and response everywhere in black American culture;

from gospel and blues, to preaching, to the rhetoric of black political leaders.

Morrison did a great deal to raise the voice of African

Americans through difficult times, but her presence at Obama’s inauguration

demonstrated how influential her own has been in giving voice to the unvoiced.

Her novels remain as a lasting testament to her influence and genius.