Listen! And I will tell you of the best of exhibitions that I saw in London yesterday…

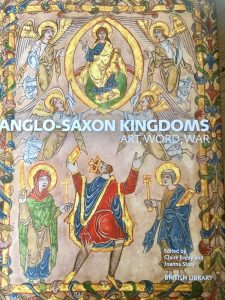

Anglo-Saxon Kingdoms: Art, Word, War at the British Library. This exhibition will end on February 19th, so I urge you to go along as soon as you can – its like will never be seen again in your lifetime. Full price tickets are £16, concessions available, booking in advance of your trip is essential. For bookings, visit: https://www.bl.uk/events/anglo-saxon-kingdoms

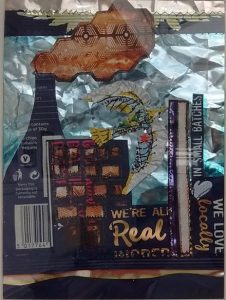

Allow around 2 hours to see this exhibition – its scope and breadth are unspeakable. This is the ‘greatest hits’ of the literary life of the British Isles between the withdrawal of Rome (early 400 CE) and the Battle of Hastings (1066). The hefty 424-page exhibition catalogue (pictured here, £40 hardback) has been essential in helping me to digest the experience as it was almost too overwhelming to absorb the detail of its 180 objects.

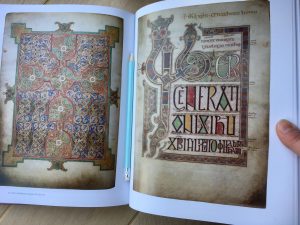

As you may expect, the bulk of the books assembled here are Latin texts created during Britain’s early ecclesiastical culture; these were copied by scribes on vellum and richly illustrated. Preservation rates are strong in these elements of the collection as these sacred texts were cared for and then often hidden in order that they survived the Reformation. These texts are numerous, but were written for the Church, in the language of the Church. Even if they had been permitted to see one of these books, the average inhabitant of these islands would not have understood them.

For me, the real high points of the exhibition were the displays of texts written in Anglo-Saxon English (or ‘Old English’) of which there are so very few in existence: not many were ever created as Anglo-Saxons were largely illiterate, yet this was the language of the ‘common folk’ of these lands, predominantly consisting of, or descending from, Scandinavian and Germanic people who had variously invaded and settled here. As the subject-matter of these books was often more secular in nature, this tiny portion of literature has not always benefitted from the protection of the Church in the way that their contemporary Latin books have. We owe a great debt of gratitude to figures such as Sir Robert Cotton (1571-1631), an antiquarian bibliophile who collected so many texts and documents in his personal library. The best-laid plans, however, go oft astray – a fire destroyed and degraded many of his books in 1731, at which point his collection was already highly regarded as a national treasure.

One of the texts which was partially destroyed by this fire is known as Beowulf (named retrospectively for its protagonist hero as no title is given). The best estimation is that this text was written down around 1000 CE, but it contains a tale handed down for many generations before that via the oral tradition. This is the first known ‘story’ from the British Isles: it recounts a tale of Danes and Swedes combining forces to do battle with monsters and dragons. This type of story, brought to Britain by an immigrant culture, came to form the modern-day Fantasy genre via the work of Anglo-Saxon scholar, J.R.R. Tolkien in the mid-20th century.

The exhibition sees the return to these shores of some texts which have not been seen in Britain for quite some centuries, such as the Codex Amiatinus – a gigantic illustrated bible which takes several people and a wheelbarrow to shift (Northumbria, created before 716 CE). Also experiencing a homecoming is the Vercelli Book (c. 975 CE) which contains several of the most important and profound poems in Anglo-Saxon and has been housed in Italy since the early 1100’s: the supposition is that a Pilgrim took it from Britain to Rome and never brought it back – to be fair, it does look heavy…

It’s not just religion and secular poetry on display here: the early British understanding of astronomy and medicinal remedies is on offer here too, along with maps, letters, accounts of Far-Eastern exploration and a collection of early music. These scores are accompanied by a set of headphones so that you can hear recordings of the music, which pre-dates the development of the major-minor key systems – chillingly beautiful in its modal inflections.

Fittingly, the through-flow of the exhibition terminates with The Great Domesday Book (c. 1086) which marked the Norman conquest’s full comprehension of the territory they had colonised following the Battle of Hastings. This account of every house, pig and slave in Britain sits beneath a short but helpful video by leading historians who give the circumstances of the book’s creation.

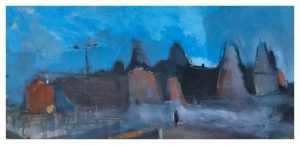

If all this isn’t enough, the exhibition is liberally studded with Anglo-Saxon ‘bling’ which adorns the walls as you move from one set of book display-cases to the next. Precious treasure from the Sutton Hoo ship burial and the Staffordshire Hoard is displayed for context – the Potteries Museum of Stoke-on-Trent is given a thankful acknowledgement as a lender to the exhibition.

The British Library has been planning this exhibition for around 7 years – it has taken this long to carefully coordinate and curate this event which has gathered together precious British books from as far afield as New York and Florence, as well as the prestigious UK collections such as are housed in the University libraries of Oxford and Cambridge – and, of course, the British Library’s own Treasures Collection. The international effort behind this exhibition corresponds with a genuine sense of the pan-European character of early Britain, and serves as a timely reminder of the fruitful nature of cultural exchange and integration – be that though the spread of Christianity from Ireland and Rome, or the multiple immigrant cultures from Northern Europe. The exhibition shows that the deeper we look into Britain’s past, the more it seems to be composed of a fascinating collage of many cultural voices.

If you like books – you really must go. If you don’t like books…. well, you really must go and see a special Doctor about that.

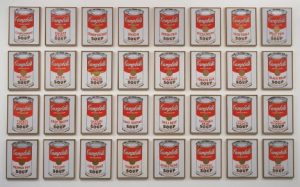

Photos: the front-cover of the exhibition catalogue, and its double-page spread of the richly illuminated Lindisfarne Gospels (Northumbria, c.700 CE).

Melanie Ebdon.