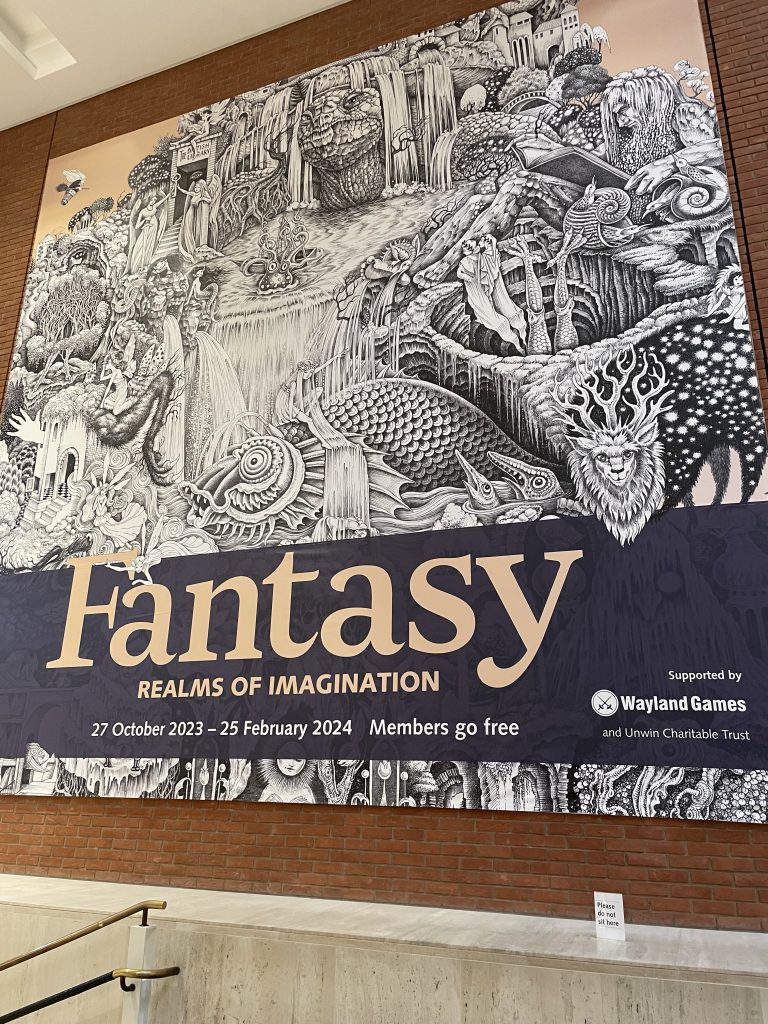

Undeterred by winter rains, I fought my way to the bustling metropolis for the British Library’s Fantasy exhibition and was handsomely rewarded by an inspirational feast for the imagination. Here are my top 4 exhibition moments, ranked and in reverse order:

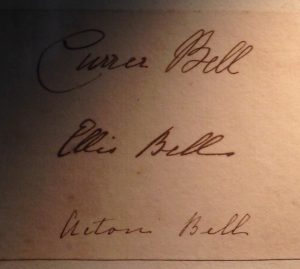

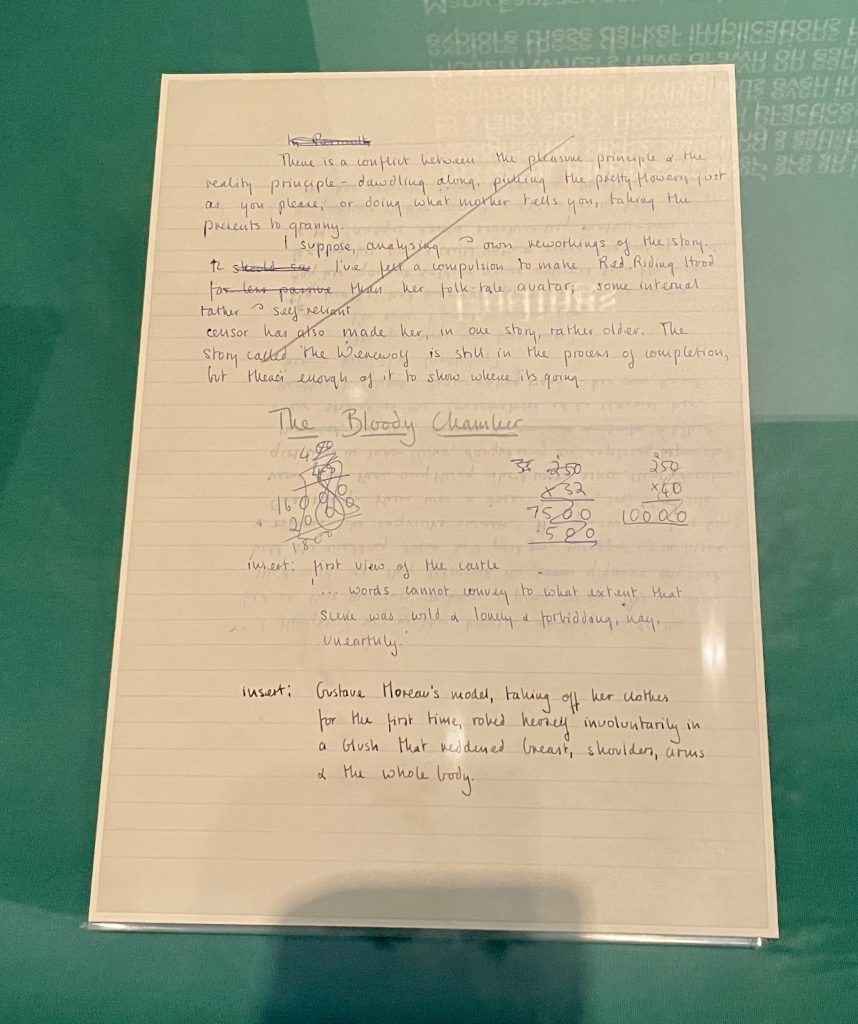

4 – Angela Carter’s notes for The Bloody Chamber:

‘insert: first view of the castle ‘…words cannot convey to what extent that scene was wild & lonely & forbidding, nay, unearthly’. There’s something arresting about seeing a story you’ve known for so long in its embryonic form. Thoughts noted, struck through, re-worded – the writer, at that point, did not entirely know where those thoughts would go and what the result would be – but you know! You have the result on your bookshelf. You read the book as an undergrad and you have taught it to your own students. I found myself thinking ‘that’s it, Ange, keep going!’…

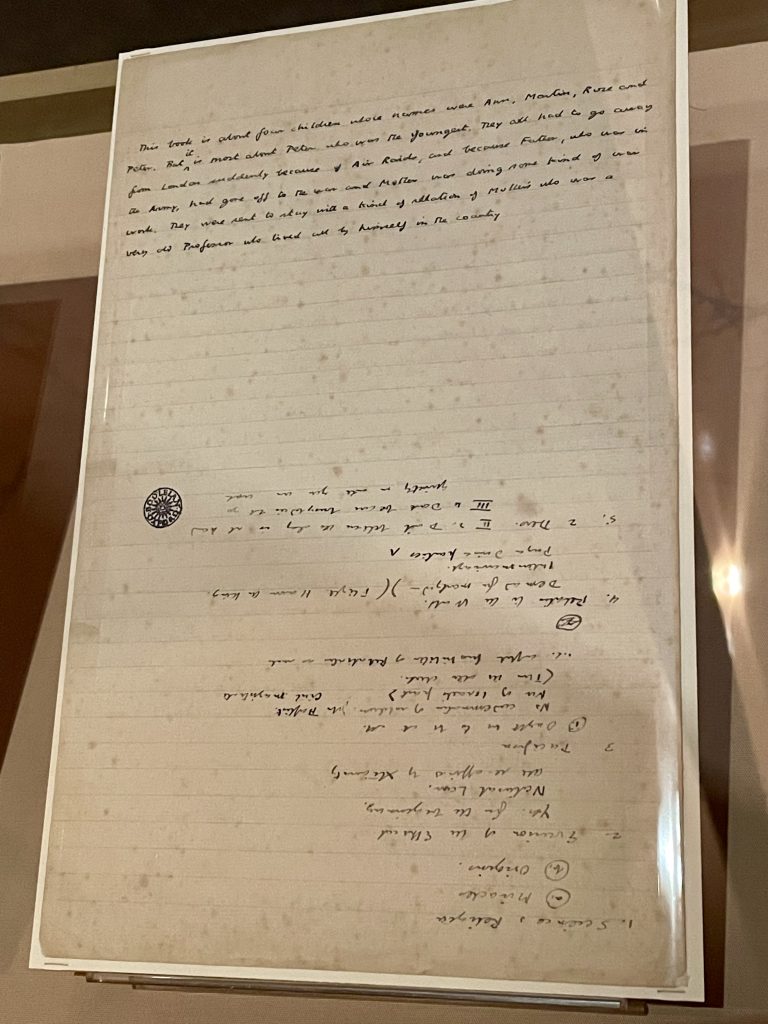

3 – C.S. Lewis’s notes for The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe:

Another amazing little bit of scribbling from C.S. Lewis – his original handwritten idea for the first book (to be published) from his Narnia world. Here, the four children have different names: Ann, Martin, Rose and Peter – ‘But it is most about Peter who was the youngest’. ‘They were sent to stay with a kind of relation of Mother’s who was a very old Professor who lived all by himself in the country’. I cannot see any mention of the wardrobe here, but the upside down notes below say (as far as I can make out) ‘1. Science & Religion a. miracles b. origins.’ The rest is a mystery to me, but so exciting to see the start of a tale that shaped my imagination from childhood.

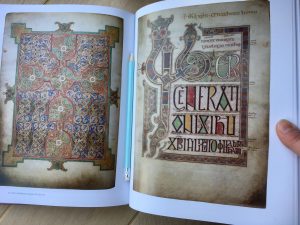

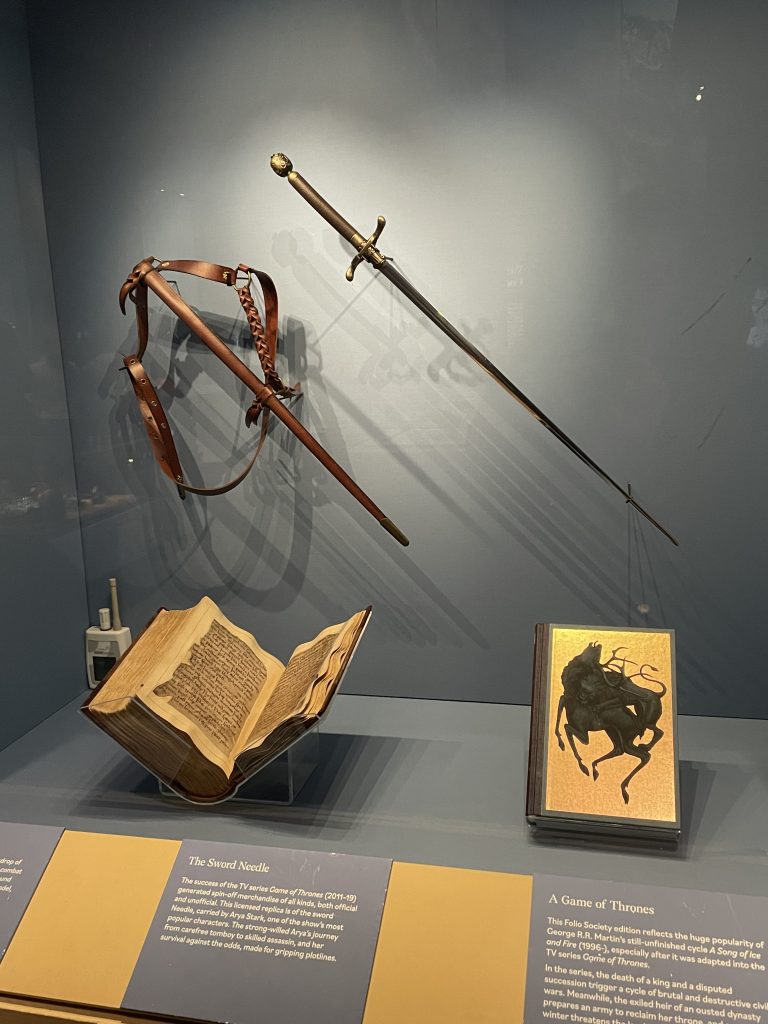

2 – Beowulf and Game of Thrones:

Fantasy is not niche. Fantasy is not new. Fantasy is, and has always been, fundamental to our ways of conveying meaning through story. Here is the oldest surviving Fantasy manuscript from the UK – Beowulf, the only manuscript of it that we know of (scribe unknown, poet unknown, date c. 975-1025 CE), with an example of contemporary fantasy writing beside it – George R. R. Martin, a book from his story-cycle A Song of Ice and Fire (Folio Society edition, 1996). A good millennium of Fantasy writing. On the wall, ‘Needle’ – Arya Stark’s sword, with harness – a prop from the popular Game of Thrones TV series based on Martin’s books.

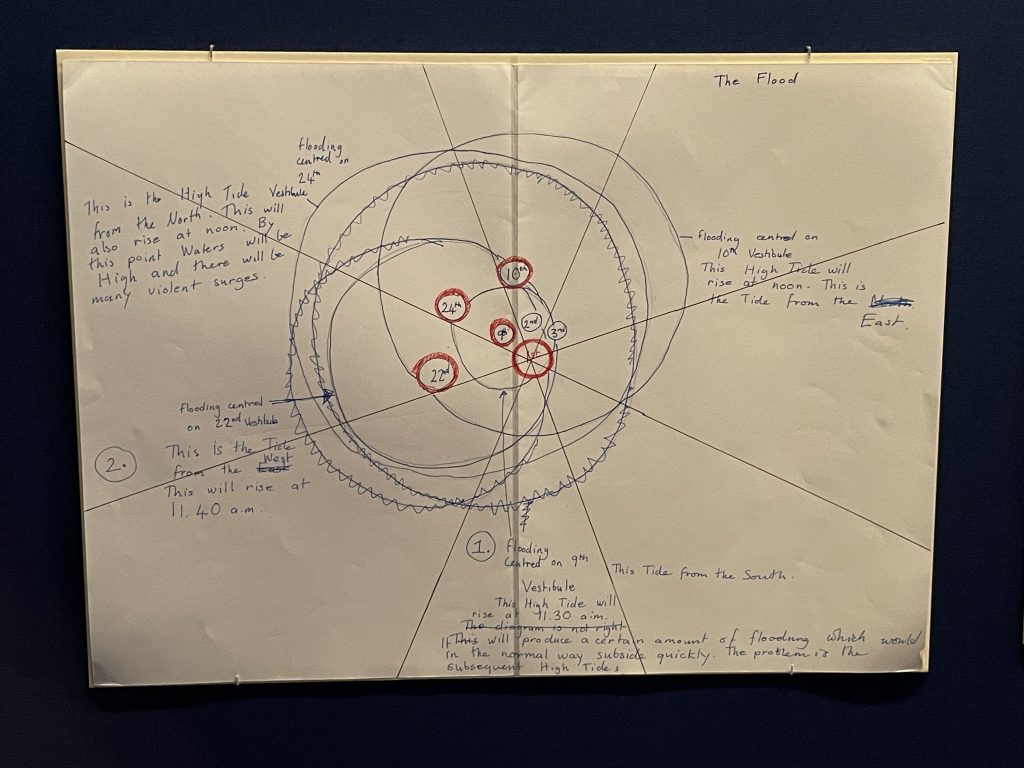

1 – Susanna Clarke’s plan of tides for Piranesi:

If you have read Susanna Clarke’s 2020 novel Piranesi, and love it and wonder/fret about how the main character is getting on just about all of the time, then it’s really hard not to blub uncontrollably in front of the notes lent to this exhibition by Susanna Clarke. These two sheets of paper detail her plan of the tides that swell around The House (Kind and Beautiful). It feels like work that didn’t really need to take place – having read the novel several times now, I have never thought too much about the logistics of the tides, even as Piranesi himself notes them – but it is work that has been done, nonetheless, just in case, just because, and it shows an attention to detail, a care and respect for Things that reverberates through Piranesi himself. There I was, in a wet, dim, windy London (not too far from Batter Sea), looking at a document that read not as a plan of a literary fantasy world but as a guide from a traveller who had inhabited another dimension. note 1. ‘Flooding centred on the 9th Vestibule. This is the tide from the South. The High Tide will rise at 11.30 a:m. The diagram is not right. It This will produce a certain amount of flooding which would in the normal way subside quickly. The problem is the subsequent High Tides’. In an age of sea-level rise, and in a week when the Trent had flooded very badly (a river which is tidal for 50 miles), we are ourselves at the Mercy of the Tides.

My jaw continues to be challenged gravitationally by the exhibition book: Realms of the Imagination: Essays From the Wide Worlds of Fantasy – a weighty tome (what else?) stuffed with short, accessible essays by giants of the Fantasy world in its academic and creative expressions (Neil Gaiman, Cristina Bacchilega, Teri Windling), images of the exhibition artefacts, and details of its astounding bespoke artwork by Sveta Dorosheva https://blogs.bl.uk/living-knowledge/2023/10/interview-with-sveta-dorosheva-artist-for-fantasy-realms-of-imagination.html